Goku's Big Adventure

The Belladonna of Sadness

Gamba's Adventure

Taro the Dragon Boy

The Golden Bird

Treasure Island

The Biography of Budori Gusuko

The Wildcat and the Acorns

Call of the Wild

Flight of the White Wolf

I Am A Cat

Laura, Girl of the Prairies

Pollyanna

3000 Leagues in Search of Mother

Lassie

1967, 39 eps, dir Gisaburo Sugii

Although the first three episodes of Goku's Big Adventure hewed close to the original manga, the series evolved into something of a gag free-for-all after the explosive success of episode four, the surrealistic and often highbrow humor of which has made this series something of a cult classic. As a result, however, the series was the victim of a bad rap by the PTA, who thought the show was potty-mouthed, and misunderstanding by viewers, who didn't get the jokes, forcing Mushi Pro to replace the gags midway in the series by a 'defeat the monster'-type formula. But ratings never recovered, and the series ended prematurely after 39 episodes, one season short of the intended 52.

Although the first three episodes of Goku's Big Adventure hewed close to the original manga, the series evolved into something of a gag free-for-all after the explosive success of episode four, the surrealistic and often highbrow humor of which has made this series something of a cult classic. As a result, however, the series was the victim of a bad rap by the PTA, who thought the show was potty-mouthed, and misunderstanding by viewers, who didn't get the jokes, forcing Mushi Pro to replace the gags midway in the series by a 'defeat the monster'-type formula. But ratings never recovered, and the series ended prematurely after 39 episodes, one season short of the intended 52.

Before the series began, Gisaburo Sugii was given permission by Tezuka to do as he pleased with the series, prompting him to go in a revolutionary new direction: Gathering the best talent around him, he declared "Down with dramatic common sense!", and set out to give the animators back the freedom of which they had been robbed by the tyranny of story; the fact that only one fourth of the episodes feature a script writer belies his intent. Indeed, Osamu Dezaki, Masami Hata and the other episode directors at the helm, many of whom cut their teeth on Goku, rapidly got into the swing of things in following with their own animatorly urges, pushing story aside and testing the limits of the new medium of TV anime with increasingly absurd gags and general craziness the likes of which would never be seen again in anime, most of which comes across as rather tame once one has seen what was achieved so early on in the history of the medium. The absurd hilarity of many of the best episodes is something which is unrivaled in all of anime, and episode 4 is undoubtedly among the funniest 24 minutes of anime ever created. The soundtrack by Seiichiro Uno, maestro of many a classic Toei film, is composed specifically for each episode. Witty, colorful, and as unpredictable as the gags, it's part of what gives the show its edge. In short, this is an important landmark in anime history as an exception to the rules.

Kanashimi no Beradonna

1973, 89 mins, dir Eiichi Yamamoto

The third and last of the Mushi Pro Animerama films, The Belladonna of Sadness is an adaptation of French historian Jules Michelet's novel of the story of Joan of Arc: La Sorcière. The obvious and salient feature of this film is the unique way in which it was animated using a blend of still illustrations and full animation. Intended for 'art house' venues rather than a more general audience like the first two Animerama films, Belladonna comes across as by far the more sophisticated and successful production, its strikingly original visuals largely responsible for the film's visceral impact. This film was in fact intended to be, literally, revolutionary: a revolution against the dominant Disney full-animation style. Unfortunately but predictably, the film languished critically and with audiences as a result, and scant few if any later anime films can be said to have carried on Belladonna's legacy of breaking new ground in animation techniques. It stands today as one of the small handful of anime films that can stand up to comparison with the most innovative work in 20th century animation, beyond mere niche (ie anime) appeal.

The third and last of the Mushi Pro Animerama films, The Belladonna of Sadness is an adaptation of French historian Jules Michelet's novel of the story of Joan of Arc: La Sorcière. The obvious and salient feature of this film is the unique way in which it was animated using a blend of still illustrations and full animation. Intended for 'art house' venues rather than a more general audience like the first two Animerama films, Belladonna comes across as by far the more sophisticated and successful production, its strikingly original visuals largely responsible for the film's visceral impact. This film was in fact intended to be, literally, revolutionary: a revolution against the dominant Disney full-animation style. Unfortunately but predictably, the film languished critically and with audiences as a result, and scant few if any later anime films can be said to have carried on Belladonna's legacy of breaking new ground in animation techniques. It stands today as one of the small handful of anime films that can stand up to comparison with the most innovative work in 20th century animation, beyond mere niche (ie anime) appeal.

In the film, the distinctive illustration style of illustrator Kuni Fukai is brought to life in a way that no other artist's work has been brought to life in a full-length animated film, blending his actual illustrations of the characters with incredibly imaginative animation which seems to ooze from the images themselves. The man responsible for this bold approach, Gisaburo Sugii, did a marvelous job of bringing these pictures to life, choosing what to use as a still illustration, when to switch to full animation, and how to make it seem natural. The director Eiichi Yamamoto in turn handles the human tragedy played out by this visual phantasmagoria with his usual good dramatic sense. The quirky folk-rock soundtrack also contributes to the film's rather medieval and otherworldly yet stylishly modern atmosphere. Overall this is truly unique film with artistic vision and an adult sensibility lacking in the first two films, with all their Tezuka-esque bathos and childish comedy. It is, however, curiously neglected even in Japan, where the first two films are much more well known. From an artistic standpoint Belladonna is their unquestionable superior, but people probably still don't know what to make of it. It's a shame, because this is one of the most original of all anime films.

Gamba no Boken

1975, 26 eps, dir Osamu Dezaki

Gamba's Adventures is a unique anime series for its exceptionally successful use of highly dynamic cinematography, fast-paced action and cunning use of the BGM score by Takeo Yamashita to heighten dramatic tension to the highest possible level. Gamba can be considered the most extreme embodiment of certain aspects of anime auteur Osamu Dezaki's rather distinctive, ultra-expressionistic style. It is very popular among Japanese fans, who consistently rank it as one of the handful of best anime of all time. The scene continuity and layout were both perpetrated by Tsutomu Shibayama, an innocuous fact which might be overlooked, but which was an unprecedented approach in anime production, and is one of the primary factors which gives the series its unmistakable visual flavor. The only two other TV series in anime history to have followed this approach are Takahata's Heidi and Marco, where Hayao Miyazaki acted the part.

Gamba's Adventures is a unique anime series for its exceptionally successful use of highly dynamic cinematography, fast-paced action and cunning use of the BGM score by Takeo Yamashita to heighten dramatic tension to the highest possible level. Gamba can be considered the most extreme embodiment of certain aspects of anime auteur Osamu Dezaki's rather distinctive, ultra-expressionistic style. It is very popular among Japanese fans, who consistently rank it as one of the handful of best anime of all time. The scene continuity and layout were both perpetrated by Tsutomu Shibayama, an innocuous fact which might be overlooked, but which was an unprecedented approach in anime production, and is one of the primary factors which gives the series its unmistakable visual flavor. The only two other TV series in anime history to have followed this approach are Takahata's Heidi and Marco, where Hayao Miyazaki acted the part.

Unfortunately, the series was cancelled after only two seasons, and the staff had evidently been planning on four, which had an adverse effect on the pacing of the series. Whereas the series started out at a leisurely pace, with a number of original episodes not in the book (many of which are among the best episodes in the series, like episodes 5, 10 and 15, which all have a curiously nonsensical and cartoony air about them reminiscent of Goku's Big Adventure, one of Dezaki's earliest involvements), right around episode 14 the story suddenly becomes focused on the journey to Noroi Island and loses the lighthearted spirit which made the early episodes fun to watch. Curiously, much the same thing happened with Goku 8 years earlier: it had bad ratings, so the series became more serious and boring in response to station demands but wound up being cancelled anyway.

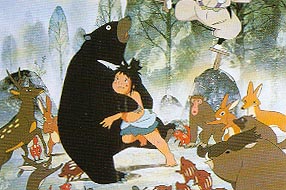

Tatsu no Ko Taro

1979, 75 mins, dir Kirio Urayama

An undeservedly neglected minor anime masterpiece, Taro the Dragon Boy was the last gasp from the once great studio that created such classic anime films as Puss 'n Boots and Hols, Prince of the Sun. While they continued to make films into the early 1980s, their backbone of great animators had already scattered to the four winds many years before, and none of these films are of any worth.

An undeservedly neglected minor anime masterpiece, Taro the Dragon Boy was the last gasp from the once great studio that created such classic anime films as Puss 'n Boots and Hols, Prince of the Sun. While they continued to make films into the early 1980s, their backbone of great animators had already scattered to the four winds many years before, and none of these films are of any worth.

The plan to animate Tatsu no Ko Taro was in fact suggested by Isao Takahata many years earlier. In the hope of regaining its faded glory, Toei invited Takahata to direct the film, and Kotabe to be animation director. However, Takahata was unable to do so because of other engagements, greatly dissappointing the staff. Instead, Kirio Urayama, a live-action director of some renown but who had no experience in animation, was chosen for the task. Although it's tantalizing to think what might have become of the film had Takahata been at the helm, Kirio Urayama's slow, measured pace gives the film a unique atmosphere and his talent cannot be denied. Further, in terms of art direction and animation direction, this film features some of the most inspired work ever to grace the big screen: Animation director Yoichi Kotabe brought to this film all of the genius he brought to the Takahata TV series Heidi and Marco, and Isamu Dota did probably some of the best work of his career as the art director, producing black and white watercolor backgrounds of striking beauty which help to give the film its mythic character. Incidentally, the novel on which this anime was based was also the inspiration for Osamu Tezuka's Hato yo Ten Made, an experimental cross between folkloric prose narrative and manga.

Kin no Tori

1987, 52 mins, dir Toshio Hirata

The Golden Bird was released as part of Toei's Manga Matsuri, but it was actually animated by Madhouse. Completed in 1984, this film was shelved for three years before being theatrically released, during which time rumours spread about it being a "lost masterpiece".

The Golden Bird was released as part of Toei's Manga Matsuri, but it was actually animated by Madhouse. Completed in 1984, this film was shelved for three years before being theatrically released, during which time rumours spread about it being a "lost masterpiece".

Although overall hardly a masterpiece, in terms of visuals alone this is certainly an anime film of great interest. It has some of the most ornate animation and creative design work of any contemporary anime movie. The highly stylized, geometrical character designs are reminiscent of a real masterpiece from an earlier era: Yasuji Mori's Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon. Sumptuous, loudly theatrical backgrounds combine with the fluid Madhouse animation to create consistently beautiful visuals in every scene. The film benefits from engaging characters like the big bird (whose flight sequence is perhaps the film's best moment), the magical robots, the amusing bat cats and the witch, all created by animation director and character designer Manabu Ohashi, who appeared on the anime scene in 1978 with the opening and ending animation of Osamu Dezaki's Treasure Island. Kawauchi Kuni was to return to Madhouse a few years later to provide the music for two other visually imaginative literary animated films: the Kenji Miyazawa OVA series released by Konami. The latter two films also share with The Golden Bird their director, Toshio Hirata, who has proven himself to be an anime director with a graphic sensiblity par excellence in the various anime projects in which he has been involved over the last two decades.

My main problem with the film would be with the script, which seems a little too strident in its portrayal of certain characters like Hans' brothers, whose over-the-top belligerence only rubs one the wrong way rather than seeming comic. When Hans finds the golden bird and decides to place it in the cage despite Lulu's warning, again, it isn't funny, it just smacks of lazy writing, and makes you feel like the writer could have put a little more effort into coming up with a slightly more plausible plot device.

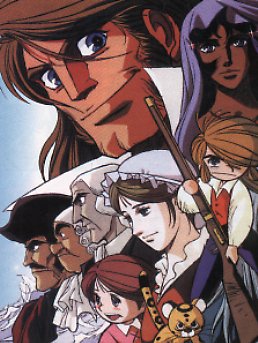

Takarajima

1979, 26 eps, dir Osamu Dezaki

Treasure Island was the followup by the legendary Dezaki-Sugino director-animation director team to their TMS-produced series Ie naki ko. Treasure Island has suitably different atmosphere and story from the latter, and the quality of drawings similarly stays relatively high in every episode, although the animation itself feels a little sparser. For good or bad, at half the length of the World Masterpiece Theater, this series doesn't have time to get boring before it is finished. The plus side to the brevity is that the fast pace keeps the familiar story moving constantly, preventing our attention from flagging. The stylish opening and closing animation was done by Manabu Ohashi, and latter-day director Ryutaro Nakamura can even be seen among the key animators in various episodes. Dezaki revels in the character of Silver, creating in him a wonderfully engaging anti-hero, a favorite character type of Dezaki's which he was to come back to again and again (for example in Cobra and Blackjack). Overall, this is a splendidly entertaining literary anime without the literary pretentions.

Treasure Island was the followup by the legendary Dezaki-Sugino director-animation director team to their TMS-produced series Ie naki ko. Treasure Island has suitably different atmosphere and story from the latter, and the quality of drawings similarly stays relatively high in every episode, although the animation itself feels a little sparser. For good or bad, at half the length of the World Masterpiece Theater, this series doesn't have time to get boring before it is finished. The plus side to the brevity is that the fast pace keeps the familiar story moving constantly, preventing our attention from flagging. The stylish opening and closing animation was done by Manabu Ohashi, and latter-day director Ryutaro Nakamura can even be seen among the key animators in various episodes. Dezaki revels in the character of Silver, creating in him a wonderfully engaging anti-hero, a favorite character type of Dezaki's which he was to come back to again and again (for example in Cobra and Blackjack). Overall, this is a splendidly entertaining literary anime without the literary pretentions.

Gusukobudori no Denki

1994, 85 mins, dir Ryutaro Nakamura

The Biography of Budori Gusko was the recipient of numerous awards including the Monbusho Selection. The original novella on which the film is based is one of Kenji Miyazawa's more famous works, alongside Matasaburo the Wind Imp, Gauche the Cellist and Night on the Galactic Railroad. The story follows the life of a young boy named Gusuko who lives in the countryside with his parents and little sister. A string of droughts and other natural disasters tear the family apart, and Gusuko is forced to leave home and seek his fortunes on his own. Driven by a desire to improve the quality of life of his poor countrymen, he eventually joins a group of scientists called the Iihatov Volcano Department, and there takes part in scientific projects to fight the natural disasters that drove him from his home.

The Biography of Budori Gusko was the recipient of numerous awards including the Monbusho Selection. The original novella on which the film is based is one of Kenji Miyazawa's more famous works, alongside Matasaburo the Wind Imp, Gauche the Cellist and Night on the Galactic Railroad. The story follows the life of a young boy named Gusuko who lives in the countryside with his parents and little sister. A string of droughts and other natural disasters tear the family apart, and Gusuko is forced to leave home and seek his fortunes on his own. Driven by a desire to improve the quality of life of his poor countrymen, he eventually joins a group of scientists called the Iihatov Volcano Department, and there takes part in scientific projects to fight the natural disasters that drove him from his home.

The story is obviously semi-autobiographical, mirroring Kenji's experiences working for years amongst the farmers of Iwate teaching scientific farming practices and fighting the inclement northern Japanese countryside. The story could justifiably be seen as problematic on a number of counts, primarily so Budori's self-sacrifice at the end, a course of action portrayed as acceptable to the scientific institution of the Iihatov Volcano Department. Otherwise, the story as rendered in this movie version successfully captures the atmosphere of charming naïveté of the scientific hopes of past generations, when Western science seemed to hold the promise of solving all of humanity's problems.

The directing of the up-and-coming new director Ryutaro Nakamura (who more recently directed the much-talked-about Lain) is indeed very satisfying. Writer and director of the film, Nakamura maintains a tight rein on the pace, and has an excellent grasp of film structure, keeping the screenplay close to the original while infusing every moment of the film with relevant detail. Most importantly and most crucial to the success of this film, his sense of drama is almost flawless: He knows just how to handle scenes of human interaction to make the interplay believable, and at all times seems to be fully aware of the ramifications of any particular scene within the whole film. The BGM is beautiful and effuses a sort of gentle pathos wavering between the minor and major keys which brings to mind Tchaikovsky.

The character designs are slightly reminiscent of Isao Takahata's Gauche the Cellist, with an honest simplicity refreshingly far removed from the self-indulgent, bland, calculated attractiveness of popular anime character designs. The animation is entirely satisfactory, and doesn't feel low-budget despite the obvious constraints of the TV special format. (Anime feels low budget only when you have a bad animation director, not a low budget.) In all respects this is a good anime film, though it doesn't measure up to the two classic Kenji adaptations, Gauche the Cellist and Night on the Galactic Railroad.

Donguri to Yamaneko

1988, 25 mins, dir Toshio Hirata

The Acorns and the Wildcat is a unique short film in picture-book format from the creator of Night on the Galactic Railroad and Gauche the Cellist. Unusually for an anime, a narrator reads Kenji's story aloud while the action is played out on the screen by a succession of warm and evocative illustrations brought to life by subtle touches of animation. If the film feels somehow familiar yet you can't put your finger on the reason why, it's probably the sumptuously minimalist animation by Yasuhiro Nagura, who was the animation director of Mamoru Oshii's artsy 1986 feature Angel's Egg. That, and Kenji's wildcat is said to have been the inspiration for Miyazaki's Panda/Totoro creature. The idea of reading Kenji's story aloud instead of playing it out as a drama is quite refreshing, and Kenji's magical language and narrative style are entirely sufficient to sustain interest. Combined with the spacey music and breathtaking art, the result is a pleasantly unassuming little gem of a film.

The Acorns and the Wildcat is a unique short film in picture-book format from the creator of Night on the Galactic Railroad and Gauche the Cellist. Unusually for an anime, a narrator reads Kenji's story aloud while the action is played out on the screen by a succession of warm and evocative illustrations brought to life by subtle touches of animation. If the film feels somehow familiar yet you can't put your finger on the reason why, it's probably the sumptuously minimalist animation by Yasuhiro Nagura, who was the animation director of Mamoru Oshii's artsy 1986 feature Angel's Egg. That, and Kenji's wildcat is said to have been the inspiration for Miyazaki's Panda/Totoro creature. The idea of reading Kenji's story aloud instead of playing it out as a drama is quite refreshing, and Kenji's magical language and narrative style are entirely sufficient to sustain interest. Combined with the spacey music and breathtaking art, the result is a pleasantly unassuming little gem of a film.

Koya no Sakebigoe

1981, 90 mins, dir Kozo Morishita

Call of the Wild tells the familiar story of a dog named Buck who is kidnapped from his cushy home, sold as a sled dog, and passed from one master to another until finally ending up in the snowy north, where he falls in with a wolf pack and returns to live in nature.

Call of the Wild tells the familiar story of a dog named Buck who is kidnapped from his cushy home, sold as a sled dog, and passed from one master to another until finally ending up in the snowy north, where he falls in with a wolf pack and returns to live in nature.

I found this to be a moving and convincing film that paints an honest picture of animal-human relations, showing that the whole picture is not always rosy. However, the film is not for the squeamish, with numerous bloody and brutal fight scenes showing dogs fighting and getting beaten, something unusual for literary anime of this nature, because usually 'literary' is synonymous with 'for kids'. Instead, the film remains faithful to the spirit of the novel without softening the edges for kiddy viewing, which in itself made the film that much more engaging for being sincere. The main characters of the film, the dogs, are portrayed entirely naturalistically (i.e. no talking), and clearly a degree of effort was put into realistically reproducing canine behavior in considerable detail. The soundtrack by World Masterpiece Theater veteran Takeo Watanabe is infectuously jazzy, if a bit unusual considering the context. The story is all compressed into just over an hour, so many details from the book are certain to have been skimmed over. The character designs and art direction are a bit crude, but the dogs are animated with great care. Aspects of the film which have made it age less well than it might have had it been handled by a different studio include the exaggerated action lines, the jerky and unrealistic movement, the dogs that literally soar through the air in fight sequences, blood that squirts all over the place and then disappears, etc. This is where the film loses to the WMT, which had much higher production quality. Nonetheless, this is still a remarkably enjoyable film, and a far more serious-minded anime literary adaptation than most of the WMT, for which it deserves a lot of credit.

Hashire, Shiroi Okami

1990, 84 mins, dir Yasuo Maeda

In Flight of the White Wolf, a boy named Lasset who lives on a farm in the rural northern US makes a perilous trek through the wilderness to a sanctuary 300 miles to the north to save the life of a gray wolf that he had raised from a puppy after an incident in which the wolf kills the family dog. The BGM in the film consists entirely of Dvorak's Serenade for Strings, making it perhaps the only anime since Gauche the Cellist to make use of a single piece of classical music as the soundtrack. The plot of the film is simple and the outcome obvious, but the atmosphere of the film is genuine, and it is very moving in parts thanks to Dvorak's music (which is scored entirely for the most emotional of the instrument groups, the strings). This is a straightforward drama about the friendship between a boy and his wolf, and pushes all the buttons you'd expect. But it's still rather enjoyable for all that (as far as it goes).

In Flight of the White Wolf, a boy named Lasset who lives on a farm in the rural northern US makes a perilous trek through the wilderness to a sanctuary 300 miles to the north to save the life of a gray wolf that he had raised from a puppy after an incident in which the wolf kills the family dog. The BGM in the film consists entirely of Dvorak's Serenade for Strings, making it perhaps the only anime since Gauche the Cellist to make use of a single piece of classical music as the soundtrack. The plot of the film is simple and the outcome obvious, but the atmosphere of the film is genuine, and it is very moving in parts thanks to Dvorak's music (which is scored entirely for the most emotional of the instrument groups, the strings). This is a straightforward drama about the friendship between a boy and his wolf, and pushes all the buttons you'd expect. But it's still rather enjoyable for all that (as far as it goes).

Wagahai wa Neko de Aru

1982, 73 mins, dir Rintaro

I am a Cat is an attempt at a basically faithful adaptation of Soseki Natsume's very famous early humorous novel about the life and death of a cat "with no name as of yet". The music consists of Vivaldi's The Four Seasons, used here and there to great effect by Rintaro to hilight ironic or pathetic moments. Rintaro's style of humor is uncannily well suited to that of Natsume in this book (though Natsume was a lot more dour in almost everything else he wrote), with its highly ironic and self-critical outlook, and the film convincingly recreates the atosphere of Natsume's novel within the confines of Rintaro's idiosyncratic directing style, which is in full array here, and has never seemed more effective. On the visual front, the cat characters appear to be slightly simplified (i.e. badly drawn) versions of the original Haruki designs, and the humans appear to be designed in an entirely different style, which lends the work a certain lopsidedness which doesn't exist in Jarinko Chie, where all the characters were scrupulously reproduced by animation director Yasuo Otsuka to bring Haruki's manga alive on the screen, as per director Isao Takahata's directive. And that, in the end, is one of the critical differences between Rintaro and Takahata: Rintaro seems essentially bound to the one style he knows, whereas Takahata is more flexible - and infinitely more profound.

Note that Etsuki Haruki is the manga artist who created Jarinko Chie, which was made into a movie and then a TV series by Isao Takahata at TMS around this time, hence the reason the cat characters in Jarinko Chie look identical to those in I am a cat.

I am a Cat is an attempt at a basically faithful adaptation of Soseki Natsume's very famous early humorous novel about the life and death of a cat "with no name as of yet". The music consists of Vivaldi's The Four Seasons, used here and there to great effect by Rintaro to hilight ironic or pathetic moments. Rintaro's style of humor is uncannily well suited to that of Natsume in this book (though Natsume was a lot more dour in almost everything else he wrote), with its highly ironic and self-critical outlook, and the film convincingly recreates the atosphere of Natsume's novel within the confines of Rintaro's idiosyncratic directing style, which is in full array here, and has never seemed more effective. On the visual front, the cat characters appear to be slightly simplified (i.e. badly drawn) versions of the original Haruki designs, and the humans appear to be designed in an entirely different style, which lends the work a certain lopsidedness which doesn't exist in Jarinko Chie, where all the characters were scrupulously reproduced by animation director Yasuo Otsuka to bring Haruki's manga alive on the screen, as per director Isao Takahata's directive. And that, in the end, is one of the critical differences between Rintaro and Takahata: Rintaro seems essentially bound to the one style he knows, whereas Takahata is more flexible - and infinitely more profound.

Note that Etsuki Haruki is the manga artist who created Jarinko Chie, which was made into a movie and then a TV series by Isao Takahata at TMS around this time, hence the reason the cat characters in Jarinko Chie look identical to those in I am a cat.

Sogen no Shojo Rora

1976, 26 eps, dir Mitsuo Ezaki & Seiji Endo

Laura, Girl of the Prairies is based on the same work as the famous American live-action TV series Little House on the Prairie. Curiously enough, it was not part of Nippon Animation's World Masterpiece Theater, even though based on a famous work of western literature, but aired on TBS while 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother, the second WMT, was airing on Fuji TV in 1976. In fact, an examination of the staff will reveal little connection between the two. This series is inferior to contemporaneous WMT series, being rather simplistic and clearly aimed at a lower age-group, but nonetheless is a good daily-life drama with a leisurely pace and story.

Laura, Girl of the Prairies is based on the same work as the famous American live-action TV series Little House on the Prairie. Curiously enough, it was not part of Nippon Animation's World Masterpiece Theater, even though based on a famous work of western literature, but aired on TBS while 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother, the second WMT, was airing on Fuji TV in 1976. In fact, an examination of the staff will reveal little connection between the two. This series is inferior to contemporaneous WMT series, being rather simplistic and clearly aimed at a lower age-group, but nonetheless is a good daily-life drama with a leisurely pace and story.

The series, while not told from Laura's POV, focuses on Laura, and does a good job of getting into her mind. Indeed, the series feels at times like a sort of second-rate Heidi; the latter, which finished airing on TV less than a year before Laura started, was clearly an influence on Laura. The main characters (the father, mother, Laura and her older and younger sister) are individualistic and well fleshed out by the script. In the final count the characters are the series' greatest asset. They come across as real human beings, and hold your interest from beginning to end.

In terms of the technical aspects, the art direction shows great attention to detail with the trappings of the era, the BGM perfectly complements the story, and the character animation is lifelike, although not very fluid by today's standards. The character designs by Mori may take some getting used to, being typically round and simple. But if the sign of a great animator is that he can convey the most nuance in the fewest strokes, then Mori succeeds in this eminently. The story pacing is also good, letting you get a feel for the family's daily rituals without letting the story lag too much (remember that this series was only half the length of the WMT), and the story itself is compelling, telling of a family that strikes out west to begin a new home on virgin territory. Episodes are episodic but this narrative thread is never lost. Finally, the overall feel of the series is very warm and memorable, making it greater than the sum of its parts.

In short, while not quite a buried diamond, this is definitely a good series in its own right which any WMT fan should consider watching, and an interesting side-note to the WMT which deserves to be more well known, especially considering this was one of only a handful of TV series in which Yasuji Mori was animation director. Episode 1 shows him at his best, creating a thrilling atmosphere right from the beginning with his trademark style of animation directing, and the backgrounds are quite beautiful; in all respects, this is a fantastic episode. Unfortunately, the rest of the series goes a bit downhill after this promising beginning, without the mark of genius which had made episode 1 so thrilling to watch. Yasuji Mori drew Heidi's character design for the Heidi pilot film in late 1973, but these designs were abandoned for the series, and Yoichi Kotabe took over as character designer and animation director, and presumably Laura was the logical continuation of many of those ideas, a sort of Heidi mk. II or Heidi à la Mori.

Ai Shojo Porianna Monogatari

1986, 51 eps, dir Kozo Kuzuha

The good news about The Story of Loving Girl Pollyanna is that the story in question is well paced. It doesn't lag too much, is fairly interesting, and the script is entirely sufficient to propel the plot. Pollyanna's character is endearing. Pollyanna, who gives us the English noun of the same name, was the name of the sunny little girl who played the game of looking for the good side in everything, especially in the things that went wrong. In the story, her kind and innocent nature opens the hard heart of her adoptive aunt and of all those she meets. The middle of the series is moving and has a surprising potential for the tragic. There are many characters, which make the series more interesting, as they weave a few subplots into the narrative. I can't make comparisons with the original, but apparently the second half of the series, in Boston, comes from a continuation. The story is not as sharply episodic as some of the later World Masterpiece Theater series. There are no qualms with the animation, which is high-quality as others have mentioned, save that body movement isn't very true to life. The character designs are what you'd expect from a WMT series; cute, but not too cutesy, and not as jarring as those in Rascal and Perrine.

The good news about The Story of Loving Girl Pollyanna is that the story in question is well paced. It doesn't lag too much, is fairly interesting, and the script is entirely sufficient to propel the plot. Pollyanna's character is endearing. Pollyanna, who gives us the English noun of the same name, was the name of the sunny little girl who played the game of looking for the good side in everything, especially in the things that went wrong. In the story, her kind and innocent nature opens the hard heart of her adoptive aunt and of all those she meets. The middle of the series is moving and has a surprising potential for the tragic. There are many characters, which make the series more interesting, as they weave a few subplots into the narrative. I can't make comparisons with the original, but apparently the second half of the series, in Boston, comes from a continuation. The story is not as sharply episodic as some of the later World Masterpiece Theater series. There are no qualms with the animation, which is high-quality as others have mentioned, save that body movement isn't very true to life. The character designs are what you'd expect from a WMT series; cute, but not too cutesy, and not as jarring as those in Rascal and Perrine.

Onto the bad news. The faces are cut from a mold -- look at Pollyanna and Jimmy side by side, look at the expressions, the eye and eyebrow placement -- they don't seem to announce individuals with individual personalities. The dialogue does little to alleviate this. The Japanese dialogue (I can't say anything about the German) lacks wit but also doesn't seem natural. Characters speak to fill in blank space, rather; they alternately speak, nag, and bawl in order to goad the storyline to move on somewhere, as one would with a stubborn burro. You know how authors sometimes say that a "character wrote itself"? Well, the author wrote these. The story itself isn't bad, it kept me watching. But Pollyanna's voice-acting in the Japanese is high-pitched and high-strung, if therefore appropriate to the dialogue she's fed. Here's a fun game you can play with your friends while you're watching Pollyanna: Every episode, place bets on who can make the closest guess as to how many minutes into an episode Pollyanna will start crying. The fewer the minutes the higher the ante. Because it happens EVERY episode. And it's something terrible around the middle of the series, because then everybody cries at one point in just about every episode, which is just about the most shameless display of heart-on-sleeve lachrymosity I've ever seen. The blatant didacticism was distasteful, too, although the bible-thumping was at a tolerable level (since it's a part of the story). At certain points even these references and the way they're attached to innocent, pure little Pollyanna, are a little disconcerting. The use of The Church in the story is just sympathetic enough to seem manipulative and slightly odious. The seemingly endless maudlin flashbacks to Pollyanna's father's dying words were a little much, too. That's the thing about this series, the director doesn't know how to paste it all together and make it compelling. It all remains distant, awkward, like today reading a play written in iambic verse. The music, by Koroku Reijirô, is okay, but has nothing on brilliant soundtracks like those in Heidi, Anne and Sara.

What's more, the whole scenario of Pollyanna going off into the city (Boston) and opening the heart of the cold-hearted people who surround her, smacks oddly of the same scenario in Heidi (when Heidi goes to Frankfurt and there has to endure Lottenmeyer). Within a few episodes of the finale, though, the degree of similarity reaches an absurd level. Pollyanna has just returned home to Beldingsville, her AUNT's country home. Out of the blue it's announced that the WHEELCHAIR-BOUND boy Pollyanna had met in Boston has a chance of RECOVERING (nothing had even been mentioned of such a possibility until then) and, to that end, his doctor reccomends that they send him to Beldingsville, a salubrious COUNTRY TOWN, to get him away from the noxious air of the CITY TOWN of Boston. Not only will the country's "FRESH AIR" help him CONVALESCE better but he will be able to see Pollyanna, whom he had LOST HOPE OF EVER SEEING AGAIN, at the same time. Perhaps I'm being overly scathing, but that was the impression that immediately struck me while watching the episode, not one I frittered up for the sake of dissing Pollyanna. In any case, this is not something that should be of concern to casual audiences. This portion of the story as much as any other can be enjoyed in and of itself. So: In the end, this leaves Pollyanna, perhaps not as good art, but as good entertainment. And, to be sure, good entertainment it is. Pollyanna targets and successfully reaches the intended audience of the WMT: youngsters. It uses self-explanatory dialogue and melodramatic body language to make nuances of emotion easily palpable to children.

Haha wo Tazunete Sanzenri

1976, 52 eps, dir Isao Takahata

3000 Leagues in Search of Mother is an emotional ride. That is the first thing that attracted me to it, I think. The series is in control of itself. It's a lack of this control for which other World Masterpiece Theater series can be docked points. Each moment serves a purpose, either in establishing mood or in furthering plot, and in establishing mood something of a far grander scale than is immediately perceivable begins to come to life. Retrospect lets the imagination run wild, just as during the series Marco's sad ramblings, complementarily, leave one entranced. This kind of journey is archetypal, as are the Oedipal feelings Marco embraces. And these feelings are the driving force behind the series at all turns -- from the early episodes of youthful rebellion against his father to his relentless Argentinian perambulation. The journey evokes many things at once, from Bunyan's vision of the soul's sojourn through the valley of the shadow of death, to Blake's kindrid collective vision or his Little Boy Lost, to the universally known, perennial story of Odysseus's desultory homecoming. Visual poetry is the only term I can think of to describe why the series is so evocative to me.

3000 Leagues in Search of Mother is an emotional ride. That is the first thing that attracted me to it, I think. The series is in control of itself. It's a lack of this control for which other World Masterpiece Theater series can be docked points. Each moment serves a purpose, either in establishing mood or in furthering plot, and in establishing mood something of a far grander scale than is immediately perceivable begins to come to life. Retrospect lets the imagination run wild, just as during the series Marco's sad ramblings, complementarily, leave one entranced. This kind of journey is archetypal, as are the Oedipal feelings Marco embraces. And these feelings are the driving force behind the series at all turns -- from the early episodes of youthful rebellion against his father to his relentless Argentinian perambulation. The journey evokes many things at once, from Bunyan's vision of the soul's sojourn through the valley of the shadow of death, to Blake's kindrid collective vision or his Little Boy Lost, to the universally known, perennial story of Odysseus's desultory homecoming. Visual poetry is the only term I can think of to describe why the series is so evocative to me.

Everything starts right with the first episode -- there is no slowness of pace either at the beginning of the series or anywhere else. And what's more, the first episode brilliantly encapsulates and forebodes the entire rest of the series, spanning the range of emotions from carefree joy to shocked desolation, and acting out the prototypical drama -- between the archetypical duo of mother and son -- of meeting and separation that Marco is to replay over and over very shortly. And this single episode acts to unleash the chain of events that will lead Marco to another continent. No lollygagging exposition here!

The music utilizes authentic instruments much of the time, so in Italy you've got accordions and violins, and in Argentina you've got guitars and flutes. The BGM is organized well and doesn't become repetitious. Oftentimes, instruments play duos or solos that are simple, authentic-sounding -- and powerfully moving. The music is an integral part of the whole, and goes a long way towards explaining why I rate the series so highly. I beleive that music is far more important a part of our everyday lives, and of our art, than it is generally credited for. And with time I have only grown to put more importance on the music in an anime. Music is the embodiment of unseen rhythms that lie behind everything, behind all human actions. And any piece of art must needs reconcile the music INTO the finished work, and communicate something on its own at the same time. I feel the music in 3000 ri does that.

The scripting is beleivable, true-to-life, idiomatic; characters are individualistic in the extreme; facial expressions are different on every single character, even on people who are just passing by on the streets, be they beggars or drunks or call girls or liverymen; the voice-acting by almost every character without exception is gripping, especially Matsunoo Keiko's performance of Marco, and both convincing and appropriate in all situations, well complementing the unobtrusive but skilled camera-work, which itself profits amply from the brilliant background paintings. What I'm trying to convey by this awful run-on sentence is how intricately and inextricably linked all aspects of the production are. The creator of the background paintings, Mukuo Takamura (artistic director of Gauche the Cellist), without whom this series would be unthinkable, deserves to be singled out for special praise for his work. He captures the light and the shadow brilliantly in every scene. Sven Nyvkyst comes to mind as a live-action analogue of Mukuo.

There is a panorama of interesting characters that come and go. Perhaps that's another boon -- that characters don't loiter around and get tiresome, as is the typical route in an anime series. The pathos of the series is linked to this, in fact. Every one of the characters comes across as an individual because of distinguishing quirks, facial tics, speech patterns, etc -- and they are all the more evanescent and Marco's plight saddening for it. Even more impressive is that the way mores in different countries -- Italy and Argentina -- in other words the way people act, is captured, and all without resorting to racist stereotypes. That is the pratfall in dealing with foreign countries in anime, that none but the most skilled and worldly of creators can avoid having to rely on such stereotypes on account of unfamiliarity with the foreign country in question. And in few anime is an avoidal of such stereotypes more exigent than in the WMT series; few beside 3000 ri were so sweepingly successful at it.

This brings up an important point: The inadvertent inclusion of Japanese quirks in an anime series that supposedly takes place on another continent. Some of the WMT have been guilty of this transgression. Mostly such is only apparent if you think long and hard about the script, but occasionally there are strange, immediately out-of-place seeming slips, like having somebody bow to somebody else in apology. Sure, Japan's not the only country that bows. But what's the likelihood of anybody but a foot-servant doing that in America? In 3000 ri, the way placards consistently display gramatically correct Spanish or Italian is but one minor detail which adds to an uncannily authentic composite picture of the foreign land in question. Without such strict realism it would have been impossible to evoke, as 3000 ri does, with as much psychological accuracy the sensation of wonder felt by a traveller in a foreign land upon seeing all the strange new sights and sounds. Marco is experiencing this bewilderment, but his tragedy is that he can never let on, that he can never let his guard down. This bewilderment is the same sensation that Bergman sought to capture in The Silence by placing his actors on a silent train running through a foreign, unknown country at war. And with this bewilderment comes a sense of adventure, of truly living. It's a sensation that any person who has travelled to a foreign land can empathize with or attest to. The traveller's, like the vagrant's or the explorer's, is a primordial situation which pits one person against all, against the external forces. This is an integral part of the "search" that many spend their entire lives at, looking for meaning, a calling, or, ironically coming back full-circle in life, mother.

In closing, this series may be a little intense for children. Each episode is emotionally draining, although the rewards are manyfold. I'm guessing that's why it was cancelled in Argentina. Heidi is a step backward in emotional intensity and therefore a step forward in overall approachability, but it's also, as a result, a less honed, less studied work of art than 3000 ri is. If Pollyanna is at one end of the spectrum of pandering to children, 3000 ri is at the other. But to go so far as to cancel it is parochialism and misguided parenting (on the part of the stations, I wonder?) at its worst. Kids can watch, but unfortunately, they're going to be challenged. They're going to have to think. They're going to have to expand their world-view and learn a few lessons without black and white, dimwitted, moralistic morals.

Meiken Rasshii

1996, 25 eps, dir Sunao Katabuchi

[Note: The following is not so much a review as a desultory and somewhat incoherent commentary I wrote in 1996, what seems many years ago now, which I reproduce here merely as a historical objêt of juvenalia]

[Note: The following is not so much a review as a desultory and somewhat incoherent commentary I wrote in 1996, what seems many years ago now, which I reproduce here merely as a historical objêt of juvenalia]

On the novel and various film versions

In the original novel, the story is that of a collie's four-hundred mile journey from the northern coast of Scotland back to her master in Yorkshire, England. Her master, a Yorkshire working man named Sam Carraclough, had sold her to the Duke of Radling in Scotland. She escapes from his mansion and makes the journey back to England, arrives half-dead, and is nursed back to health by Sam's son Joe. The original film version, made in 1943 with a male collie named "Pal", had Elizabeth Taylor as co-star and was such a success that a five-year contract with Pal and his trainer Rudd B. Weatherwax was made, and a whole slew of Lassie films followed, including The Sun Comes Up with a screenplay by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, author of The Yearling. Following these successes Pal became a star to outshine his older canine celebrity, Rin Tin Tin, living in air-conditioned dressing rooms and with other luxuries fitting a hollywood star.

The anime version

A young pup is found on the side of the road by young John, who passes by her by chance twice in a hurry before noticing the miniscule ball of fur gazing at him unassumingly as he comes and goes. Finding no collar and seeing that the pup is in a sickly condition, he takes her home and nurses her so that he can search for her master when he has a chance. Progressing slowly from this discovery, the episodes find Lassie growing gradually bigger, and everyday life goes on around her as she absorbs all the wonders it has to offer, almost like a toddler. The pace is leisurely and there is delicate attention paid to the subtle details of everyday life. Lassie causes trouble as a curious explorer, getting into the flour pot and making a mess of the kitchen. John, having been warned so by his mother at the outset, discoveres the difficulties of raising a living thing, and finds himself annoyed at Lassie's antics. But Lassie is ever-faithful and shows an almost human intelligence (the first trait from the novel I've spotted) on certain occasions. Each episode progresses thus and is usually a situational one-shot story, though always bringing forth important elements of John or Lassie's character. Both John and Lassie are the main characters, one could say. Most importantly, however, the anime is almost a different beast altogether from the novel because the book was the story of Lassie's 400 mile journey in search of her master, but that of the anime is of a different sort; it is padded, as Heidi and the other WMT series are, with the day-to-day life of "a boy and his dog." (written on March 24, as of having seen up till episode 8; my feelings as of later on into the series below)

The animation is overall exceptionally high quality. Character movement is, as ever, very human-like and close attention is paid to small details of facial expression and body-language. Nippon Animation has gotten proficient with the use of "loops" of animation, and likely due to the director, Katabuchi Sunao, the timing of the loops has a consistently good impact and the overall organization of the episodes feels very "tight" or well-paced. Not much happens in each episode, but my low expectations have been far surpassed, what with the high quality production, the leisurely pace, the many touching moments and the realistic angle taken to portraying everyday life. (why do I feel like a movie critic?) The director, however, is a newcomer to the World Masterpiece series. The character design, by Morikawa Souko, is the same as that of Tico, but apart from sharing the same skin, what's underneath is a world apart.

--- New thoughts following Lassie's "hoisting" --- (written Sept. 14)

It's been about a month since the last episode of Lassie (ep. 25: Aug. 18) and two weeks since the first episode of "Remi," Lassie's preemy successor. I won't dwell on my misgivings about the outcome of the series and the tradition-breaking startup of Remi the homeless [girl] (Ie naki ko Remi) punching in just a bit early on the WMT-series' hitherto yearlong timetable, because I don't really know what to make of it. It's simply vaguely disconcerting. Why break tradition now? Actually, it seems less like a swift snap than a leisurely crumbling. Thinking about it now, the length of the WMT series seems like it's determined by some sort of quadratic function; one delineating a downwards arc. And so far it's led us all the way from the magic number of 52 (Get it? 52 weeks in a year! Cray-zee!) down to juust past the midway point that leads us to the magic number of zero: 25. (hmm.. 25... second attention span? Now I get it!)

Why complain? From hearsay, Remi is damned cute! And she's voice-acted by Horie Mitsuko, the famour singer. Who could ask for more! If it takes bending the gender of a main character here or there so's to make the series more titillating to watch, not to mention cutting another series clean through the middle--razzafrazzn "boy and his dog"--so's to start up the new, more appealing, re-hashed re-animation of an already popularized story,--guaranteed audiences! yay! (Waitasecond, isn't there a flaw in that reasoning? Who wants to RE-watch a story they're already familiar with? Maybe I'm just too demanding.)--then, why, I'm all for it!

Who says that there seems to be something terribly wrong about apportioning a grand total of three episodes to the portion of the story that was the very NUCLEUS of the original novel (Lassie's voyage home)? Aww, the stinkin' original wasn't that great anyways, so they might as well make up something new! What's that? Even so, it wasn't even very convincing and the pace of events OBVIOUSLY screamed "I've been cancelled," you say? Bah, you want a long, convincing continuting storyline? Go watch some Marmalade Boy or some Dragonball (n).

...Actually...

To return to the (far up) above-stated comments about the series after having seen the first eight episodes of it, I have to admit that after having seen the next eight, my congenial opinion was wrenched a few notches downwards. By the teens, the episodes in the series seemed to have fallen into a pattern by which each episode was wholly predictable simply by the clues provided in the "next episode preview." This wasn't because the previews were thoughtlessly hashed together with enough information to extrapolate the total content, but because the episodes effectively fell into a pattern of reliance upon hackneyed and formulaic storylines. Combined with the fact that--for, one aspect of the production of a show can sometimes prove its saving grace--the directing left one with the impression of watching something far less convincing than Scooby Doo with characters about as colorful as the set in a Samuel Beckett stage production, there was nothing to rescue this series for me. Simply put, there was nothing convincing about the way the people acted. They didn't act like people; they acted like anime characters. That which attracted me originally to the WMT wasn't pastiche action sequences and frills tailored to stimulate an audience of Pavlov's Dogs. It was the fact that the characters in the anime lived lives that I could relate to, and "acted," by the directorial skills of individuals like Isao Takahata--and even lesser directors like Endou Seiji, Saito Hiroshi and Koshi Shigeo, who collectively directed Rascal in 1977 no less convincingly than Takahata did "Heidi" and "Marco" during the two years before--, in a manner no less nuanced than the way we all "act" in the play called real life. The story seemed led on not by a predestined outcome into which the details of the story as a whole would have to be tucked and cut, but by the random, natural "flow" that leads us all in every day life to unpredictable new places. Having not seen any of the intermediate WMT tv series (from Tom Sawyer all the way down to Nan and Miss Jo, in fact), I can't comment on the directing for anything but the very early and the very recent series, with 3000 Ri and Romeo perhaps as the two most fitting representatives from these respective extremes of the timeline. However, the difference between the two ends which is evident to me seems nothing short of the constrast between black and white. One end is imbibed with the essence of what the WMT set of series has been to me "since the very beginning," and the other seemingly lacks this essence completely. All that's left is the shell, the legacy of the novel-basis for the tv series. And yet even this seems to be crumbling away before my very eyes.

Consider: Tico was an ORIGINAL STORY. This is so glaringly antithetical to the very concept for the World Masterpiece Theater series of tv series that I can't but imagine that Nippon Animation *must*, by Tove, have been thinking *something* to bridge that gap in logic that wavers there before my feet and threatens to swallow me into the depths of resigned indifference; but frankly I can't.

Consider then: The story of Romeo bears nearly no resemblance to the story in the original novel, and even the story in the anime was rushed near the end and cancelled and postponed ruthlessly in mid-series in order to meet Fuji TV's demands to make way for variety (game) shows and stand-up comedy.

Consider next: Lassie, following in Romeo's tracks (does this imply that this is a new trend?), bears little resemblance to the original novel, and in order to meet with the broadcasting network's demands, by the time that the anime finally got to the part that had anything to do with the original novel, they had to hurry the storyline and cut the series off prematurely. Padding a series would be nothing new and nothing scandalous for the WMT series; Heidi was doing it before the series even started. But it was just that: padding; not re-writing. Nowadays, not only do the series seem to be determined by the temporal and unpredictable whim of the broadcasting network, but the stories themselves, besides--to me, at least--lacking convincing directing, have strayed from the unspoken charter of the "World Masterpiece Theater." It seems almost as if, nowadays, the stereotypical elements which are conceived as the attributes of a WMT tv series are either being cannibalized from a book and farcially referred to as animated versions of that book, or else--in the case of Tico, which is the ONLY case thus far, of course--being used as molds to make up an anime series that isn't even based on ANYTHING--except ratings.

I hope it did occur to you, dear reader, that my comments on Meiken Rasshii in the top part--praising it--are the complete OPPOSITE of my comments in the bottom part of this page--pounding it. This is partly because I had not been exposed (within the past decade and a half or so) to the tv series which came out at the very beginning of the "World Masterpiece Theater" lineup (like Heidi, 3000 Ri and Rascal) but had a chance to watch them or re-watch them, as the case might have been, just recently. Now that I have, I have a point of comparison, and the differences between Lassie and these shows were far too glaring for me to maintain a favorable opinion about Lassie from that point on. Effectively, watching these old series and this new one so temporally close to each other was the perfect way of comparing the differences between them, and I for one can definitely identify a directorial style that characterizes the both of the two periods ("then and now") that Heidi and Lassie represent.

Series length was not a consideration back at the beginning of the WMT, when each series for the first few years was the set length: 52 episodes. That was part of the gimmick, in fact: One series a year, for the ENTIRE year. Of recence, it's the SERIES LENGTH which has become the deciding factor for what makes up a tv series. And this method's spontaneous and self-limiting way of guiding the progression of a story--as proven by its wielding upon Romeo and Lassie--doesn't seem very conducive to the making of a successful tv series. As for that phrase "directorial style" that I brandish so ambiguously, I can only keep my explanation about what it consists of short by pointing to the difference in quality that separates Isaac Asimov's sci-fi writing from L. Ron Hubbard's. It's a difference that's similar. It is, I suppose, a question of originality, and who had it, and when. Theoretically, there could be just as much originality in the WMT these days as there was "back then," but why isn't there? Or is there, and I'm just too bitter to notice it? In either case, the one thing that I find justifiably embittering is Fuji TV's policies. I suppose that everything else is a matter of personal taste.